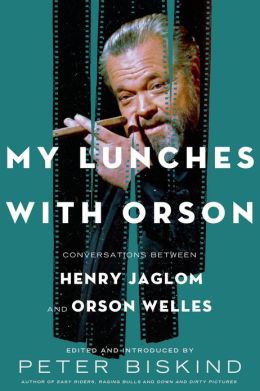

My Lunches with Orson.Conversations between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles. Edited and with an Introduction by Peter Biskind. Henry Holt and Company, 306 pp., $28

In this collection of short lunchtime talks--tapas, if you will-- you get the kind of Rabelaisian stream-of-consciousness concoction that could only be delivered by a man wearing “bifurcated tents to which, rather idly, lapels, pocket flaps, buttons were attached in order to suggest a conventional suit.” (Gore Vidal’s memorable description of Orson Welles’ late-era costume, as quoted in Peter Biskind’s introduction.) Within the ambiance of late-seventies-early eighties Ma Maison we are treated to a series of conversations between two champion talkers--the legendary Orson Welles, and his spunky sidekick Henry Jaglom. (For the record, while I’ve always been underwhelmed by Henry Jaglom’s films, he proves a stimulating foil to Orson Welles here.) The waiters come and go; celebrities mingle; meanwhile the history of Hollywood’s golden age is recounted, in swift and sometimes spiteful bursts, by one of the world’s master storytellers.

I must say, I loved this book so much more than I expected. The conversations, taped at Orson Welles request by Henry Jaglom, have been masterfully edited by Peter Biskind. We get the most delicious, unfiltered gossip, but also a sharp sense of environment. Most importantly, a character emerges: the aging boy genius, still pushing for the next big project, but in the meantime enjoying leisurely meals and angling for another lucrative commercial. (These were the Paul Masson years, after all; a contract which provided Welles major income for this period. In an amusing aside, he talks about how low-rent the Masson advertising execs were, and how much they resented his automatic attempts to improve the copy even as he spoke it.)

We learn about the evolution of Hollywood through the prism of the Ma Maison chicken salad:

OW: Don’t get tiresome about the chicken salad.

HJ: Why am I being tiresome, Orson? I want to get it the way it always is, without the capers. The waiter doesn’t understand.

OW: This is the way the chef makes it now.

HJ: They keep writing in the papers that, ever since Wolfgang left, this place has gone downhill. And his restaurant, in turn, has become the number-one one. He’s begging me to get you to come to it.

HJ: They keep writing in the papers that, ever since Wolfgang left, this place has gone downhill. And his restaurant, in turn, has become the number-one one. He’s begging me to get you to come to it.

OW: I’ll never go.

HJ: Why?

OW:: I don’t like Wolgang. He’s a little shit. I think he’s a terrible little man.

OW:: I don’t like Wolgang. He’s a little shit. I think he’s a terrible little man.

HJ: Why?

OW: I don’t know. God made him that way. What do you mean, “Why?”

And against the bustling restaurant backdrop, celebrities are sighted, summoned, gossiped about and rebuffed. Jack Lemmon stops by and chats for a chapter. Richard Burton and Liz Taylor are sent back to their own table, much to Henry Jaglom’s chagrin. The two friends touch on innumerable topics drawn from Welles 50+ years on the public stage, but, inevitably, certain names keep floating to the surface: John Houseman, enjoying a maddening career surge at the time, consistently unkind to his former Mercury Theatre partner; Rita Hayworth, partly because of Jaglom’s fascination with Welles’ gorgeous former wife; Citizen Kane, of course; and, most amusingly, Welles main Shakespearean competition, Laurence Olivier. In Welles’ book, this book, no one could be stupider, vainer, or foist more pig-headed interpretations on an innocent public than “Larry”:

HJ: How is Larry? Has anyone heard anything more about his health?

OW: I hear all kinds of stories, none of them very cheerful. He has three kinds of cancer. It’s particularly a shame, because Larry wanted to be so beautiful. I caught him once, when I came backstage to his dressing room after a performance, he was staring at himself with such love, such ardor, in the mirror. He saw me over his shoulder, embarrassed at my catching him in such an intimate moment. Without missing a beat, though, and without taking his eyes off himself, he told me that when he looked at himself in the mirror, he was so in love with his own image it was terribly hard for him to resist going down on himself. That was his great regret, he said. Not to be able to go down on himself!

OW: I hear all kinds of stories, none of them very cheerful. He has three kinds of cancer. It’s particularly a shame, because Larry wanted to be so beautiful. I caught him once, when I came backstage to his dressing room after a performance, he was staring at himself with such love, such ardor, in the mirror. He saw me over his shoulder, embarrassed at my catching him in such an intimate moment. Without missing a beat, though, and without taking his eyes off himself, he told me that when he looked at himself in the mirror, he was so in love with his own image it was terribly hard for him to resist going down on himself. That was his great regret, he said. Not to be able to go down on himself!

This is a big ego, but surprisingly, the flip side of that ego is a major fragility and, frequently, an open-heartedness and compassion towards the other players. For example, it’s obvious both Jaglom and editor Biskind want him to strike back at Pauline Kael, who, in truth, did him a gross disservice in her essay on Citizen Kane. When Jaglom brings it up, Welles just nods--she was wrong--but continues, “I love Pauline, because she writes at length about actors. Which nobody writing about movies does. II think she’s wrong a lot of the time, but she’s always interesting.” .Refreshing, particularly given the venom regularly directed her way by powerful men who found themselves on the business end of her pen.

The book conveys the depressing hustle of Welles late career, as Jaglom and he plot his next move, only to meet disappointment after disappointment. Jaglom, to be honest, seems more hopeful about the prospects than Welles at this point, who is always glimpsing the failure in any possible success. This portion of the book reaches it’s heartbreaking nadir in a meeting with an HBO exec who offends Welles with her indifference. “When I get that dead look, I’m dead!, he fumes.” “I can’t do it.” We witness the whole sorry thing.

The book conveys the depressing hustle of Welles late career, as Jaglom and he plot his next move, only to meet disappointment after disappointment. Jaglom, to be honest, seems more hopeful about the prospects than Welles at this point, who is always glimpsing the failure in any possible success. This portion of the book reaches it’s heartbreaking nadir in a meeting with an HBO exec who offends Welles with her indifference. “When I get that dead look, I’m dead!, he fumes.” “I can’t do it.” We witness the whole sorry thing.

His fatal ADD is on full display in these Ma Maison lunches, it’s true; but so too is the brilliance that allowed him to shrug off one of the greatest movie of all time at age 25.

Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles

No comments:

Post a Comment